A Diary Entry from 1764

With a little more time on our hands than usual, and over 750 years of history at Elmore, what better way to while away the hours than by rummaging through the attic and sharing with you our findings; Something we’ve been longing to do more of!

We’ve had such fun pulling out dusty boxes and flicking through ancient photographs, diaries, war relics, art, textiles and so much more. Elmore Court’s heritage is rich in history and we are so excited to share some with you.

Are you sitting comfortably? Then we shall begin…

The first of our ‘stories from the attic’ is a diary entry dating back to 1764 by 5th baronet of Elmore Court, Sir William Guise.

This impressive first hand account of adventures long ago has recently come to us from historian Paul Butler and his wife who over some time have been transcribing the diaries of Sir William found here at Elmore.

It’s said that the diaries arrived at Elmore Court in 1860;

“These journals came into my possession through an unknown correspondent who sent them to me without communicating his name. G V Guise Elmore Court 1860”… A little mystery there!

Who is Sir William Guise?

Let us first give you a little background on who Sir William Guise of Elmore Court was.

William Guise; 1737–1783, was the 5th Baronet of Elmore and Rendcombe, the son of Sir John Guise, 4th Baronet.

William was a British politician and between 1763 – 1765 he undertook the Grand Tour, where on his travels met famous English historian, Edward Gibbon.

Gibbon later went on to publish his most important work, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire and it is from this trip we have found the wonderful story of how Guise and Gibbon crossed the Alps.

A Bumpy Ride

William Guise wrote a wonderfully full account of his Grand Tour – fuller than Gibbon’s – and it’s these diaries we are able to share with you today.

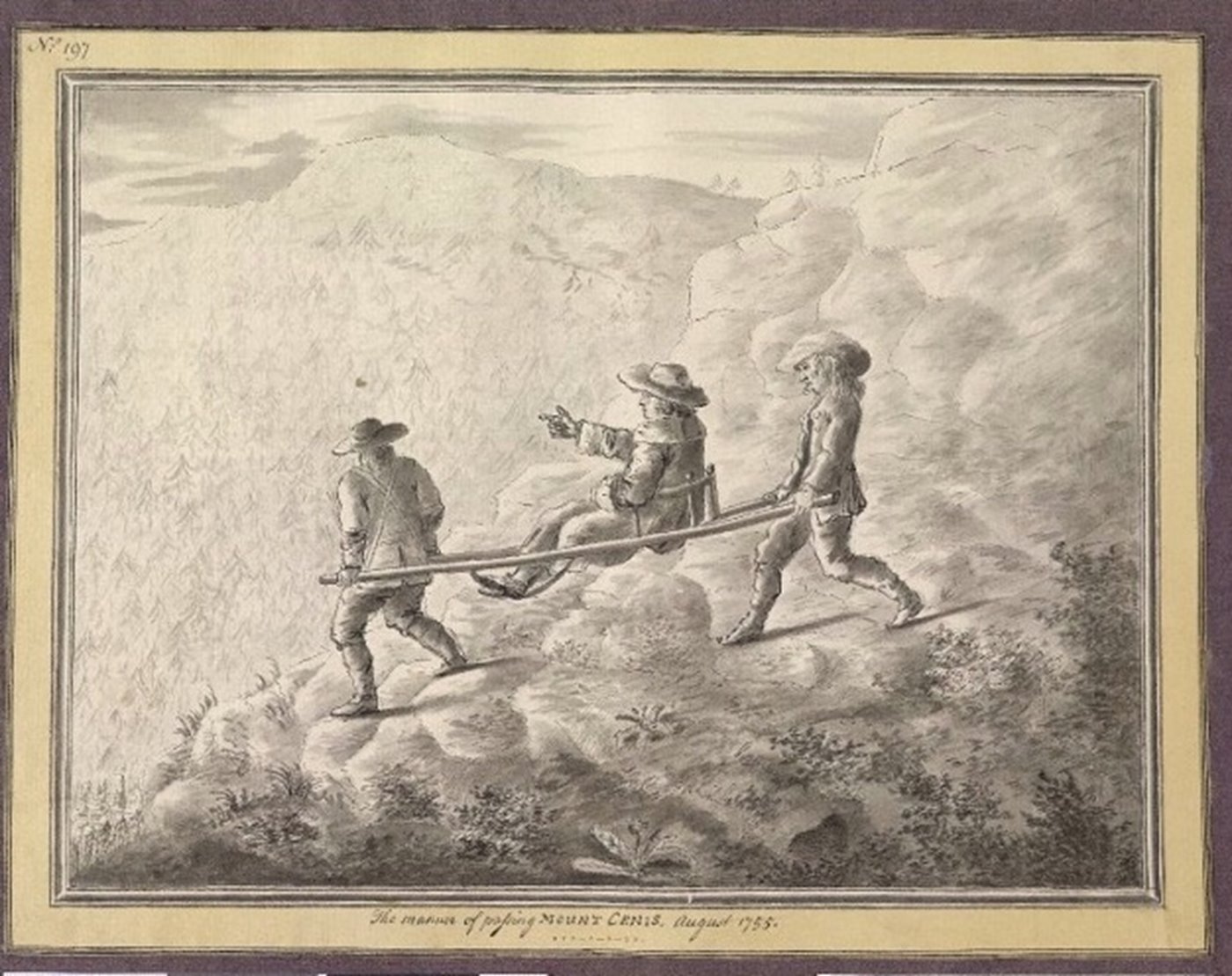

From his journals, we have learned how difficult it was to travel to Italy in the 17th century – getting over the Alps was a particular problem! Luxury travel was vastly different prior to the developments of the 20th century, and travel by chair (carried by workers, or chair men as they were known) seemed to be the first class option…

Guise, however, rode part of the journey by mule, but when conditions were too bad for mule riding, he was carried on a type of sedan chair. Gibbon – who was ‘less of a jockey’ – was carried on these chairs for the entire crossing.

William’s diaries tell of the pairs’ difficult undertaking and include some fascinating details about the pay of the chairmen and how they survived if there was an avalanche… Coincidentally they travelled in late April, making this almost exactly 256 years ago today…

April 1764

We left Lanebourg about 6 o’clock this Morning, myself mounted on a mule, my friend Gibbon being no great Jockey preferred a Chair. This Chair is only a Seat made of Rushes & Cords, placed between two long poles, it has a low back & arms to it: There is a board between the two poles for to support your feet & prevent their hanging down. They are light, & well contrived for carrying. You take 4 or 6 men, who change at fixed distances, and carry you an amazing pace.

From Lanebourg to La Ramasse

Which is near the highest part of the Mount Cenis is a League, the hill is pretty steep and one should not be able to go up it without winding very much.

This side of the Mountain is covered with snow from about 4 to 6 or 8 feet deep.

Where we went was a narrow path made by the Mules: It was exceedingly slippery, having frozen hard in the night. La Ramasse is the place where people coming down on this side commonly make use of a small kind of sledge, in which they come down in about 10 minutes. You have a man in it with you who guides it and stops it easily by means of a Chain and stick on each side.

Living under the snow

The plain begins here and continues two small leagues to La Grande Croix. A little way from La Ramasse, we saw where a few days before there had been an avalanche, or great quantity of Snow, which breaking from the side of the Mountain, is forced down by the wind, and becomes so large that it often covers the plain 8, 10 or 12 Feet deep. They don’t happen often on this Mountain, but when they do, snow inevitably buries ev’ry thing that is so unfortunate to be in its way. My Muleteer told me very unconcern’dly that they always provided themselves with a large piece of bread, least they should have occasion to live under the snow for two or three days. People have been taken out after 4 days living under the snow. A League from la Ramasse is La Maison de Postes, where the chair men commonly stop to rest themselves. We bought some excellent Cheese here made upon the mountains, which we sent to M. de Mezery. About half a L further is the Hospital. A curate lives here, and people who by the badness of the weather are obliged to lay on the mountain, are well taken care of.

Pilgrimage to Mount Rochemelon

At la Grande Croix, I quitted my mule, and went in a Chair to Novalese which is 2L further. The road is so very stony, uneven, and in many places so steep and full of holes, that it would be dangerous to go down on a mule.

On the left hand of this place is Mount Rochemelon, believed to be the highest Mountain of the Alps. On the Top of it there is a Chapel, where Thousands of people climb over Ice & snow, to hear Mass which is said there ev’ry year, on the fifth of August. Their superstition or Devotion however, often costs them very dear, as many of them are commonly lost or frozen amongst the snows.

By Chair to Novalese

We found almost all the Snow on this side the mountain thaw’d. The Mountain is not near so steep as on the other side, but from its unevenness and roughness, is much more disagreeable. I had but two men to carry me, but ‘tho I crossed over some of the steepest and worst places, they never made a false step, ‘tho they went very fast. I fancy that the road is much better than in the time of Mr Keysler as we were never obliged to get out of our Chairs, tho the road winds very much.

Half a crown for carrying!

The pay of a chairman from Lanebourg to Novalese is no more than 50 sols per man, or about half a crown English, which is certainly too little considering the distance & hardness of the work. Indeed, they commonly get something more from the people they carry, which they well deserve.

I cannot say that they are easily contented. One of Mr Gibbon’s chairmen asked him for something for having carried his sword & cane, and for having lent him a pair of Gloves, tho he had already given them a Guinea above their pay.

It is not so surprising when one considers how many of them there are, and how little they have to do.

At this time there were more than 120 at Lanebourg, & 150 at Terriera, and at Novalese, who have nothing else to do but to carry for seven months in the year.

We dined here and set out afterwards for Susa, which we reached with ease in an hour and a half.

The road is a little rough, but otherwise very good.

The diary finishes at the end of October 1764 in Rome, but their Tour does not finish for another 7 months, so, there may be some more rummaging in the eves here needed!

We hope you have enjoyed this little story as much as we have and stay tuned to see what else we dig out…

Love as Ever, Team E x